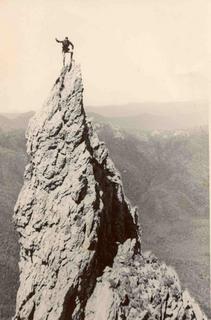

Federation Peak

Federation Peak One of the few remaining unclimbed summits in Australia, Federation Peak in southwest Tasmania, became the focus of postwar attention in the south. As early as 1946, Tasmanian Bill Jackson had attempted to reach the top and on a second attempt in January 1947 with Leo Luckman, got to within 60 metres of the summit. Carrying no rope, they were forced to turn back in bad weather. It was left to a team from Geelong College in Victoria—Bill Elliot, Fred Elliot, and Allan Rogers, led by John Bechervaise—to reach the summit on 27 January 1949 by what is now called the Bechervaise Gully. The team completed their ascent during a spell of perfect weather, climbing a chimney on the southeastern face. Bechervaise described the climb:

For the first one hundred and twenty feet there was a long lead with an awkward step out of a “sentry- box” across a sloping slab, but safety of the party was assured by a “running belay” through a chock-stone wedged deep in a crack. Above this there is the first good stance, after which a slight overhang must be negotiated within sixty feet or so. This is fairly strenuous. After this, the climb becomes much less difficult and a very steep gulch, amply provided with holds, leads, in about four hundred feet, to the summit.The first woman to climb the peak was Shirley Ward, who led a team to the top the following year. Bechervaise went on to become a distinguished Antarctic explorer, as well as a consultant to the Australian outdoors magazine, Walkabout.

Picture: Len Brazall on a gendarme near the summit of Federation Peak in 1953. Jon Stephenson collection.